If ‘history has a habit of repeating itself’ then in some parallel universe the Tasmanian should beware, for on the horizon is a ship full of ‘black fellas’ patriotically bound to drive them from their land. They’ll round up who they can, then sweep a human chain across the island. Some will be shot on sight, some will be forcibly separated from their families, some will be captured and dragged to colonies to perish in a pool of heartache. No native will remain free. Also aboard that ship will be the black fella’s convicts; the mad and the bad will be poured into the penal system to accelerate, exaggerate and incubate their disdain for the common good.

Tasmania’s history is plagued by the almost total, genocidal obliteration of the Australian Aborigines. Since it formally apologised (the first Australian state to do so) there is a natural remorse, but the damage of my forefathers is irreversible. Today, full-blooded Tasmanian aborigines are confined to the museums of many and the memories of ghosts. As a Brit the impact that the infamous British Empire has had on the world never fails to astound me. The wounds inflicted yesterday are still weeping today.

One thing that really bemuses me is how me and my compatriots are not the most hated nationality in the world. In China, India, Nepal, Indonesia and Sri Lanka – to name but a few – England is as fashionable as anything. I’ve seen shops whose sole existence is to sell England paraphernalia (and I’m not talking souvenirs). Quite why I’ve never completely understood. Some days I see it as ‘Glory Supporting’, a term that defines those who naïvely turn and follow the (perceived) best team in the league.

South East Tasmania was a real education, not least because my time there began to feel like a school trip. It wasn’t just the persecution of the Aboriginal people of Tasmania, but of the circles of power that hovered in and around the former penal colonies.

My journey here began in state capital, Hobart. I’d long had romantic notions of Hobart, the mere name rolled off my tongue like a trickle of spring rain. I pictured her white walls rolling off the hillsides into a quaint and chatty port. Small. Cosy. Affable. Although most of this was true, my imagination was polluted the moment I saw the city sprawling urgently up the banks of the Derwent River. Its central quaintness had somehow been tainted by tourism, sushi and Myers. I can’t blame Hobart folk – why should they miss out just because of my fleeting romanticism. The city also reunited me with John the Swede who had become snagged on a young Bavarian called Kate. I met John 18 months ago watching a Nepalese sun rise over the Himalaya, in the following months he became an integral character in my Sri Lankan storyboard and is one of those folks I just know will remain a long term friend.

My journey here began in state capital, Hobart. I’d long had romantic notions of Hobart, the mere name rolled off my tongue like a trickle of spring rain. I pictured her white walls rolling off the hillsides into a quaint and chatty port. Small. Cosy. Affable. Although most of this was true, my imagination was polluted the moment I saw the city sprawling urgently up the banks of the Derwent River. Its central quaintness had somehow been tainted by tourism, sushi and Myers. I can’t blame Hobart folk – why should they miss out just because of my fleeting romanticism. The city also reunited me with John the Swede who had become snagged on a young Bavarian called Kate. I met John 18 months ago watching a Nepalese sun rise over the Himalaya, in the following months he became an integral character in my Sri Lankan storyboard and is one of those folks I just know will remain a long term friend.

After an evening of merriment I bade farewell to both John and Kate and also to my parents, who had hitched a ride for 10 days. The folks were jetting off to my elder sister and family in NZ, meanwhile Reb and I were descending further into the Tasmanian wonderland, to Port Arthur on the south-eastern Tasman Peninsular.

After an evening of merriment I bade farewell to both John and Kate and also to my parents, who had hitched a ride for 10 days. The folks were jetting off to my elder sister and family in NZ, meanwhile Reb and I were descending further into the Tasmanian wonderland, to Port Arthur on the south-eastern Tasman Peninsular.

Port Arthur is a former penal colony and set among an area awash with historical suspense, criminal beauty and wicked wildlife. The actual site was chosen because you have to cross a narrow land bridge to access the peninsular, therefore escapes were tough. The isthmus was named Eaglehawk Neck and was strung with a chain of vicious canines (some even placed on platforms out at sea). They weren’t there to tear apart would-be escapees, but to raise the alarm for the guards. The stone complex of Port Arthur itself is somewhat decayed today, it stands like all nationally adored ruins; torn yet reeking with fortitude within vast and well kept grounds. Since Reb and I inadvertently bypassed the ticket office (ironically breaking into a prison) we decided to reinvest and join the evening Ghost Tour. By far the best thing about this was to see the ruins lit up. As it happened the tour group of 25 or so was infected by a fifteen year old boy who plainly fancied his own mother – at every opportunity for suspense, he produced a not-so-smart-aleck heckle and I pray he’s now plagued with nightmares.

Port Arthur is a former penal colony and set among an area awash with historical suspense, criminal beauty and wicked wildlife. The actual site was chosen because you have to cross a narrow land bridge to access the peninsular, therefore escapes were tough. The isthmus was named Eaglehawk Neck and was strung with a chain of vicious canines (some even placed on platforms out at sea). They weren’t there to tear apart would-be escapees, but to raise the alarm for the guards. The stone complex of Port Arthur itself is somewhat decayed today, it stands like all nationally adored ruins; torn yet reeking with fortitude within vast and well kept grounds. Since Reb and I inadvertently bypassed the ticket office (ironically breaking into a prison) we decided to reinvest and join the evening Ghost Tour. By far the best thing about this was to see the ruins lit up. As it happened the tour group of 25 or so was infected by a fifteen year old boy who plainly fancied his own mother – at every opportunity for suspense, he produced a not-so-smart-aleck heckle and I pray he’s now plagued with nightmares.

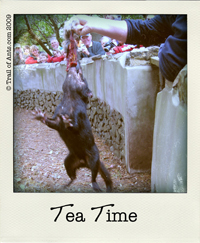

The day we left Port Arthur we quenched our first for devilment, with none other than its homebred marsupial the Tasmanian Devil. Once Tasmania’s answer to the late Steve Irwin fed a pack of three a few kilos of wallaby thigh and possum belly we were instantly enthralled (and Reb’s vegetarian). The Devils are themselves in danger from a horrific, contagious facial cancer so they’re no longer fed road kill (of which Tasmania is famed). They were much less ferocious than I’d expected. Sure, they barked at each other during feeding and devoured every last bone, gristle and grain of their meal but I couldn’t help but think of them as big rats. There were a thousand questions being fired at the guy, so the only one I could think of was “has Taz the cartoon done anything for his real life compadres?” It turns out they did very little financially, although naturally they raised the profile and also allowed the brand to be used on merchandise to fund the research and recovery centres.

The day we left Port Arthur we quenched our first for devilment, with none other than its homebred marsupial the Tasmanian Devil. Once Tasmania’s answer to the late Steve Irwin fed a pack of three a few kilos of wallaby thigh and possum belly we were instantly enthralled (and Reb’s vegetarian). The Devils are themselves in danger from a horrific, contagious facial cancer so they’re no longer fed road kill (of which Tasmania is famed). They were much less ferocious than I’d expected. Sure, they barked at each other during feeding and devoured every last bone, gristle and grain of their meal but I couldn’t help but think of them as big rats. There were a thousand questions being fired at the guy, so the only one I could think of was “has Taz the cartoon done anything for his real life compadres?” It turns out they did very little financially, although naturally they raised the profile and also allowed the brand to be used on merchandise to fund the research and recovery centres.

This region of Tasmania succeeded in every category, though for me it remains largely unexplored. It’s a result of Tassie being so fulfilling that we simply couldn’t see everything. Like usual, we’ve left something for the day we return. However this region will forever be the start of my Australian education, a place where I attempt to understand the rights and wrongs of the forerunners to the infamous whinging poms.

Are you surprised by the reception of you and your countrymen while on the road? How much of the history of a place do you like to know before visiting there? Share your thoughts with fellow readers via the comment thread below.

You must log in to post a comment.